Critique: The Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000 and the (draft) Social Forestry Rules, 2000

Critiques and insights of the environmentalists and ethnic communities of Bangladesh on the “Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000” and the “(draft) Social Forestry Rules, 2000”. 2001, English, 80 Pages, Paperback | Tk.75 / US$5

The critique presents a critical position and gives insights into the environmentalists and ethnic communities of Bangladesh on the “Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000” and the “(draft) Social Forestry Rules, 2000”. The stated intention of the amendment act passed by the parliament in 2000 and the resulting rules are to promote “social forestry”.

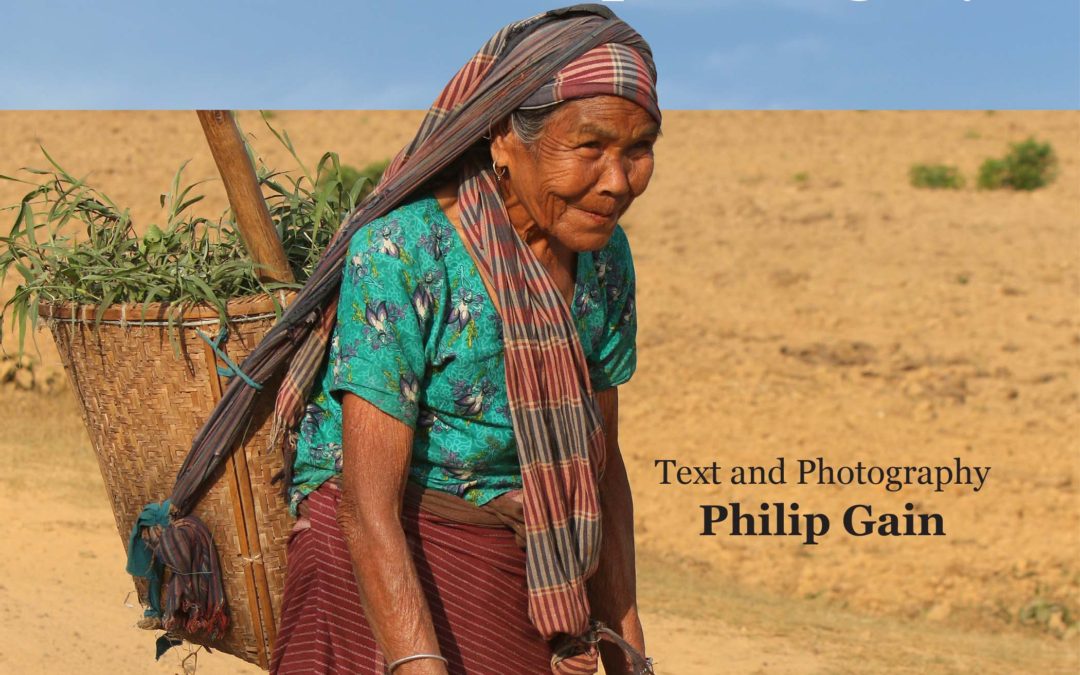

The environmentalists and Adivasis complain that commercial and industrial plantations have been established in the name of “social forestry”. They have termed the “Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000” and the “(draft) Social Forestry Rules, 2000” as being “anti-people, anti-environment and anti-national interest” and rejected the new laws. With information, photographs and reflections, the critique helps one understand the opposition of the environmentalists and ethnic communities.

The critique compiles workshop report, its resolution and two papers, “A Critique to the Forest (Amendment) Act of 2000 and the (Draft) Social Forestry Rules of 2000” by Raja Devasish Roy and Dr. Sadeka Halim and “Background and Context to the Forest (Amendment) Act, 2000 and the (draft) Social Forestry Rules, 2000” by Philip Gain.

Publication Details

Published: 2001

Language: English

Paperback: 80 pages

Editor: Philip Gain

Price: Tk.75 / US$5