Professor Rehman Sobhan, chief guest, speaking at the inaugural session.

A significant percentage of 165 million people of Bangladesh face discrimination and exclusion—socially, economically, politically—for various reasons such as ethnic identity, situations close to slavery, occupation, casteism, culture, geographical locations, landlessness and eviction from their homesteads. They are, on the one hand, deprived of equal opportunities guaranteed by the constitution to all citizens; on the other, they are handicapped by a series of social, economic and political problems. The marginal and excluded people among the citizens of Bangladesh include different communities who are victims of casteism, ethnic minority groups, tea communities, Bede, Bihari, sex workers, bisexual or transgender people, Kaiputra, Jaladas, people with disability, people living on the fringe or in char land (river island), Bawali and Rohingyas. The people of all these ethnic identities and occupational groups are at risks of being excluded because they are already deprived of their legitimate rights. The people who are marginal and excluded face deprivation in terms of leading normal life, secure permanent jobs, income, resources, access to loans, housing, education, skills, cultural capital, welfare state, citizenship and equal rights before law, democratic participation, human treatment and dignity.

Four organizations implementing the project organized the convention in LGED Bhaban, Agargaon, Dhaka on 20 and 21 June 2019 to highlight the issues of social exclusion and discrimination in Bangladesh and explore a roadmap to lift these communities out of poverty and enshrine their human rights. The participants to the convention—as many as 400—represented more than 50 ethnic and marginal communities.

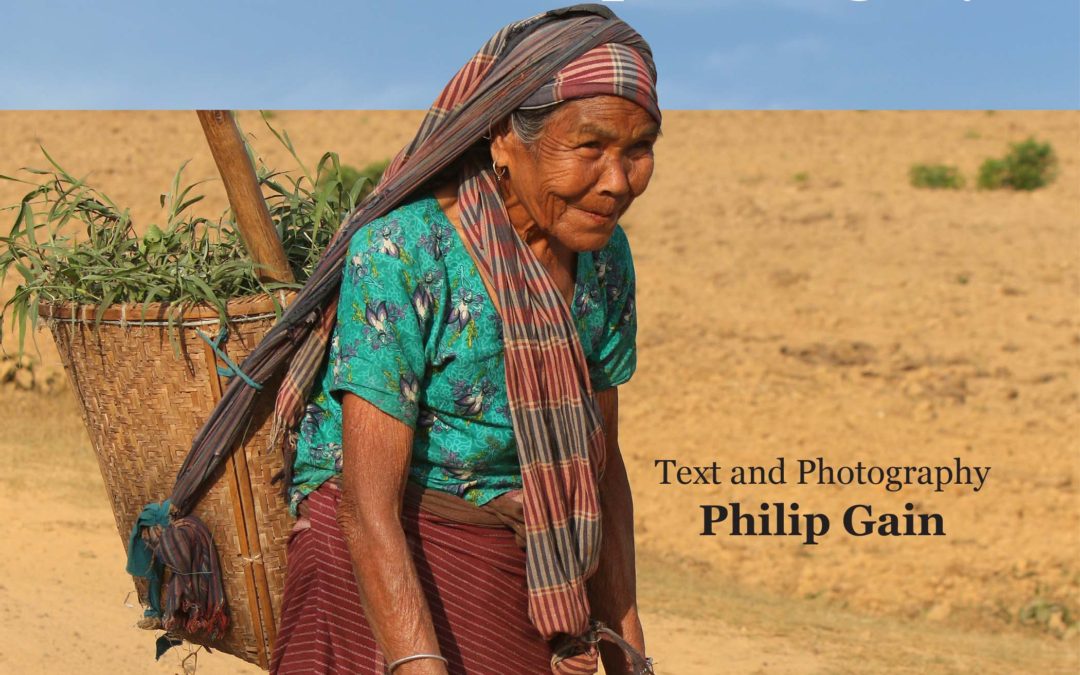

The convention had begun with an inaugural session in which a panel of experts spoke. They reflected on the keynote paper presented by Philip Gain and shared their expert opinions and insights from their lifetime professional experience to set the tone of the subsequent workshops in the two-day convention and to put the discussion on exclusion challenges in perspective.

Professor Rehman Sobhan, an eminent economist of the country and the chief guest at the inaugural session, was apprehensive in his reflections on exclusion challenges as well as marginalization in Bangladesh. “Unlike India, Bangladesh has fewer resources and political power concerning the excluded and marginal people,” said Prof. Sobhan. “The marginal communities must acquire political power along with increasing their capabilities to end discrimination against them.”

He made several recommendations to enshrine the rights of the marginal communities and tackle the exclusion challenges. “Protection of customary rights to land of the Adivasis according to legal instruments is necessary. There are several organizations working on it. An institutional framework consisting of partnerships among the civil society organizations and the political groups is crucial to protect their land,” suggested Prof. Sobhan.

Prof. Sobhan stressed on the modernization of tools for different occupational groups—Harijans, Kaiputra and Jaladas and urged the government and development organizations to adopt innovative approaches, e.g. small-enterprises concerning specific occupational groups to empower these communities. “The government has different social safety net programmes. Ensuring participation of the marginal and excluded groups in these programmes is crucial. It is also important to allocate sufficient amount for them in the national budget and think innovative ways to scale up their capacity,” said Prof. Sobhan.

The guests at the inaugural session are showing the book, “Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony” after its official launch.

The guests at the inaugural session are showing the book, “Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony” after its official launch.

Prof. Rounaq Jahan, distinguished fellow at Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), was critical while reflecting on the marginal and excluding groups in Bangladesh. “Anthropological survey like in India is absent in Bangladesh to make the ethnic and excluded communities visible,” Prof. Jahan pointed out. “The ethnic and marginal communities have different problems and no single solution can help them tackling the exclusion challenges.”

She stressed on understanding the problem trees of these communities and urged the government to take affirmative actions for them. She also stressed on the protection of customary rights of the ethnic communities on land. “Formation of a separate ministry and separate land commission that will work with other related ministries is necessary for the protection of land of ethnic communities of the plains. Besides, an umbrella organization is required to scale up their bargaining skills.” Prof. Jahan, concerned about the situation of the tea workers exclaimed, “From the British era until now, owners have changed in the tea garden. However, the life of the tea workers is still the same.”

In his keynote presentation, Philip Gain, gave an overview of the ethnic and excluded groups and people who face discrimination are at the risk of exclusion. “There are many communities other than adivasis in Bangladesh who face discrimination and social exclusion due to ethnic identities, religions, occupations, casteism and captivity. These communities include tea workers, Harijans, Bede, sex workers, Bihari, Kaiputra (pig rearing community), Jaladas and Rishi. Many of them are considered untouchables,” explained Gain.

Gain stressed on generating accurate statistical accounts on the ethnic and marginal communities. “In Bangladesh, the state agencies lack right orientation and methodologies to generate accurate statistics on the ethnic and marginal communities,” alerted Gain. “The government, in a gazette notification dated 19 March 2019, has published a list of 50 ‘khudra nri-goshthi’ (small ethnic groups) to replace the schedule in the Khudra Nri-goshthi Sangskritik Pratisthan Ain, 2010 (The Small Ethnic Groups Cultural Institution Act 2010). However, we have found around 80 communities only in the tea gardens. Twenty-three of them are on new government list as small ethnic groups. The argument for inclusion of many small ethnic groups apply to more than 50 other groups who are not on the government list yet.”

Gain stressed on the protection of land rights of the adivasis. He was critical about the functioning of the land commission in CHT. “The land issue in Modhupur sal forest area is complex. Only the Garos and Koch were the exclusive occupants of the Modhupur forest at one time of history. But the demographic picture has dramatically changed today. In our recent surveys in 44 forest villages in Modhupur, we have found out that 61.11% of the inhabitants in these villages are Bangalees, 33.47% are Garos and 5.42% are Koch. Only 13% of the Bangalee households have title deeds (CS and RoR) for their homestead land, which is only 4.19% for the Garos. The percentage of households having recorded high or chala land is much lower—4.18% (Bangalees and Garo together). In case of high or chala land again while 4.83% of the Bangalee households have such recorded land, it is only 2.61% for the Garo households. In case of low or baid land the Garo households are ahead of the Bangalees—while 9.67% of the Bangalee households have recorded low land, 11.17% of the Garo households have such land.” Gain informed that forest cases skyrocketed in the forest villages since the introduction of social forestry in place of natural forest. Gain demanded for a separate land commission for the plains land Adivasis.

In his welcome address, Joyanta Adhikari, executive director, Christian Commission for Development in Bangladesh (CCDB) spoke on the significance of mainstreaming the ethnic and marginal communities and ensuring their inclusion in the national budget and planning. He demanded for the inclusion of all small ethnic communities of the country in the upcoming national census 2021. Besides, he stressed on the importance of formulating specific policies for the protection of land of ethnic communities.

Rambhajan Kairi, general secretary of Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU), spoke on the tea workers’ condition. “Many of the communities living in the tea gardens do not have state recognition. Their invisibility indicates their identity crisis. Their languages and cultures are also in danger of extinction. They fall behind the majority Bangalee population,” explained Kairi. He also spoke on the generational deprivation of the tea workers and discrimination in the Bangladesh Labor Law 2006. “Bangladesh Labour Law 2006 is highly discriminatory. According to the law, a tea worker has to vacate his or her land on which s/he has lived for generations. The tea workers do not own any land. Where will they go after they vacate their only living place?” questioned Kairi.

Dr. Harishankar Jaladas, a novelist and writer, reflected on history of casteism and social exclusion in India. “There are many communities in Bangladesh that lag behind in comparison to the majority Bangalee population. Their access to government services is limited. A country will not culturally, economically and socially develop if the marginal communities are left behind,” exclaimed Dr. Jaladas.

Audrey Maillot, team leader, Governance, Delegation of the European Union shared EU’s views on marginal and excluded communities. “European Union supports civil society organizations to get organized and promote human rights. It is determined to give voice to the voiceless. This national level convention is a platform for the representatives of the marginal and excluded communities to share how they feel.”

The chair of the inaugural session, Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman, executive chairman of Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and former advisor to the caretaker government, reminded in his remarks: “Leaving no one behind has become a state agenda. It is now being pronounced at every sphere. However, the ethnic and marginal communities are invisible in the national statistics, social thoughts and they lack state attention,” explained Dr. Rahman. “The main objective of our initiative is to make the marginal and excluded communities visible. Besides, it is also important to break the cycle of exclusion and challenges these communities face.”

“Saving the environment has become a national agenda across the world. The Adivasis of Bangladesh have experience of living in the forest for hundreds of years. It is important to understand their traditional knowledge and use them to find a sustainable solution for the coexistence of human and nature,” alerted Dr. Rahman. He also stressed on the establishment of a resource centre on ethnic and excluded communities, which will work as a knowledge hub on their life, society and the rights.

Marginality and Exclusion Issues Discussed

Seven parallel sessions held during the two-day convention covered wide-ranging issues of the marginal and excluded communities—identity, culture and languages; ways to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for the marginal and excluded communities; understanding international instruments and national laws; innovative approaches in understanding and analysing the problems of the excluded communities; understanding micro-realities of forest and commons in Modhupur; land rights of the marginal and excluded communities; strategies for protection of the marginal and excluded communities. In the final plenary sessions reports of parallel session were presented.

Dhaka Declaration

‘Leaving no one behind’ is commitment that Bangladesh makes for achieving the SDGs agenda. Keeping this in mind, the convention came to an end with the adoption of Dhaka declaration. The declaration calls for elimination of all forms of discrimination. The participants to the convention—around 400 representatives from more than 50 ethnic and excluded communities—gave their consent to Dhaka declaration. A committee, formed in advance, drafted the declaration taking into consideration that the issues, concerns, demands and recommendations raised and made in conventions, consultations and workshops throughout the project period. Key demands and recommendations made on issues in the declaration are state recognition of the ethnic and excluded communities, official mapping to generate accurate statistics on their number and population, constitutional recognition of communities that are not Bangalees, legal protection, necessary amendment to discriminatory labour law, ending wage deprivation and income disparity, ensuring education to the children of the marginal and excluded communities, formation of a separate land commission for the plains land Adivasis and tea workers to grant them land rights, scaling up attention to decent work condition particularly of the tea workers, recognition of customary land rights, state and non-state actions against land grabbing, recognition of mother languages, rapid settlement including compounding of forest cases, and budget allocation for scaling up skills of communities that have fallen behind.

Celebration of Culture

A cultural festival was piggybacked with the convention. In the evenings of 20 and 21 June 2019 seven cultural teams from among the Garo, Santal, Telegu, Mandraji, Rajbhar, Monipuri, Baraik, Mahle, Paharia communities and one team from Transgender (Hijra) performed their unique traditional songs and dances. The Santal cultural team welcomed the guests with famous Dasai (welcome dance) of the Santals in the morning of 20 November 2019.

The cultural teams stood out because of their colorful costumes and unique performances. The magic of Babul Rabidas added an extra flavour in both convention and cultural evenings. The Mahle and Paharia cultural teams portrayed their traditional occupations and religious beliefs through dances and songs. The stick dances of artists from tea garden were stunning.

What amazed the visitors to the cultural evenings were lectures on resistance of ethnic and marginal communities through cultural forms, research and writing. On the first day Professor Tahmina Ahmed of University of Dhaka spoke on Santal resistance in the British era through cultural forms. She stressed on the importance of history in developing resistance. “History is the tool of resistance. We must rely on our history to stand for our rights. The last word of our resistance should be equality where no one shall be regarded as marginal or excluded,” exclaimed Professor Ahmed.

On the second day of the cultural festival researcher and Novelist Dr. Harishankar Jaladas spoke on resistance of the marginal people through research and writing. He emphasized on

Mahale cultural team at the cultural program.

Mahale cultural team at the cultural program.

building real life characters in novel to represent the marginal and excluded communities. Researcher and educationist from Dinajpur, Dr. Masudul Hoq also spoke on the second day.

Report by James Sujit Malo and Rabiullah with Philip Gain

Dhaka Declaration-2019

Adopted at the National Convention on Discrimination,

Exclusion and Rights of the Marginal and Excluded People

Held on 20 and 21 June 2019

We, different ethnic and marginal people, tea workers, Harijans, Rishi, Jaladas, Kaiputra, Bede, sex workers, Robidas, Transgender (Hijra), Bihari, human rights defenders, government and non-government organizations and researchers who have been working together for a long time and participated in the national convention on discrimination, exclusion and rights of the marginal and excluded people organized by Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC), Christian Commission for Development in Bangladesh (CCDB) and Gram Bikash Kendra (GBK) on 20-21 June 2019 at LGED Bhaban, Agargaon, Dhaka have adopted this declaration, which will be considered as Dhaka Declaration.

A significant percentage (approximately six millions) of 165 million people in Bangladesh face discrimination and indignity for their ethnic identity, occupation, casteism, untouchability, cultural differences, geographic locations, captive situation and various other reasons. Bangladesh has drawn attention of the world as a role model of development. However, the marginal people have difficulties in treading the same path of development as equal citizens of Bangladesh. As a consequence, these communities live in distress under extreme poverty. Bangladesh cannot be a good model of development leaving these people behind. It is to be noted that ‘Leaving no one behind’ is a key commitment of Bangladesh as regards SDGs.

We reiterate our commitment for elimination of all forms of discrimination against the marginal communities through this Dhaka Declaration. Following are our major demands and recommendations.

1. We demand the state recognition for all ethnic and marginal communities of Bangladesh on one hand and on the other want the concerned state agencies to generate accurate statistics on their population. The government, in a gazette notification dated 19 March 2019 under the Khudra Nri-goshthi Sangskritik Pratisthan Ain, 2010 (The Small Ethnic Groups Cultural Institution Act 2010) has increased the number of small ethnic groups to 50 from its previous list of 27 (including three duplications). However, according to recent research, there are still around 50 small ethnic communities who are left out from the government list. We demand inclusion of these communities in the government list. We strongly recommend that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) generates accurate statistics on these communities in the upcoming census in 2021. We are committed to provide all possible supports in this regard.

2. We strongly recommend that the government provides constitutional recognition, legal protection and scales up privileges for safety and protection of the ethnic communities and marginal groups.

3. Bangladesh Labour Law, 2006 allows tea workers to unionize only at the national level. This is a legalized discrimination. The labour law is also discriminatory for the tea workers in relation to casual leave, earned leave, gratuity and eviction from the residence. We demand for appropriate and immediate amendment of the labour law to end discrimination against the tea workers and their families.

4. A common problem that the tea workers and Harijans face is wage discrimination and income disparity. We strongly urge the government to immediately take appropriate measures in this regard.

5. We strongly demand for setting up of sufficient number of public primary schools on urgent basis so that the children of marginal communities—tea workers, Harijans, Bede, sex workers and Jaladas are not deprived of education. We also demand for introducing quotas in universities for the children of marginal people.

6. The people of the marginal communities, in many instances, do not get decent and safe work condition. They are also deprived of government healthcare. We strongly demand for ensuring appropriate work condition, health services and financial incentives to these marginal people.

7. Tea workers and Harijans are completely landless. The percentage of landlessness among other marginal and small ethnic communities is also high. It is urgent to increase their access to khas (public) land. We strongly demand that the government provides the tea workers and Harijans ownership of the land they have been living on and using for more a hundred years. We also strongly support the demand for establishment of a separate land commission at the auspice of the state to ensure the land rights of the tea workers and other landless marginal communities.

8. We strongly urge the government to sign the ILO convention No. 169 to ensure the customary land rights of the Adivasis who have been living on the forest land for generations. We also request the government to implement other international instruments and national laws in favour of the marginal communities.

9. We fervently request the Planning Commission of the Government of Bangladesh to furnish specific information in the next progress report on SDGs about progress made in development of the marginal communities.

10. We strongly demand for separate and special attention on the marginal and excluded people in the upcoming eighth five-year plan of the Government of Bangladesh.

11. We strongly urge for strengthening prompt the government and non-government response in investigating and reporting on issues related to human right abuses—land grabbing, reservation of forest, land acquisition and requisition, etc.

12. We demand for increased government efforts to protect and promote more than 40 languages other than Bangla spoken by different ethnic groups in Bangladesh and to promote at least primary level education in their mother languages. At the same time we demand that the society and the state work for nurturing and flourishing of the cultures of the ethnic communities.

13. Forest cases are a matter of great worries for the people of Modhupur and other forest areas in Bangladesh. Most of these cases are allegedly false or intentional. We appeal to the Government, Forest Department and the Judiciary to settle these cases as soon as possible.

14. The marginal and excluded people have become weak because of misdeeds, injustice and discrimination they have faced for generations. They need to develop skills through technical training alongside general education in order to participate in the race for development. We request the government to build their skills through vocational training in consideration of needs and demands of different marginal communities with government budget. We also urge the government officials to be more considerate to these people. We strongly demand active participation of the marginal communities in the formulation and implementation of development projects that involve them.

15. The Government of Bangladesh has different social safety net programmes to reduce poverty. We urge for ensuring legitimate demand and opportunity for the marginal and excluded people in these programmes.

16. We demand that the government commits to ensure civil rights including land rights of the marginal people and we demand allocation of necessary and sufficient budget for this.

Ensuring political, social and economic protection to the marginal communities is a major challenge for Bangladesh. It is not expected that all debates about the definition, identity, number and population size of different marginal and excluded communities will come to an end any time soon. But the state and non-state organizations must play their role right to bring changes in the lives of people who are among the extreme poor and deprived of their legitimate rights. However, all marginal communities do not face the same difficulties. It is to be noted that the difficulties they face are not uniform and there is no single solution for all of them. We expect sincere commitments of the state and others concerned to ensure rights and protection of the marginal and excluded communities. At the same time, we, different marginal communities and those who work with them commit to work from our individual and collective capacities to keep up all initiatives and dynamisms to ensure the philosophy, “Leaving no one behind” in Bangladesh.

21 June 2019

On behalf of more than 400 representatives from among more than 50 small ethnic and marginal communities.

The guests at the inaugural session are showing the book, “Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony” after its official launch.

The guests at the inaugural session are showing the book, “Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony” after its official launch. Mahale cultural team at the cultural program.

Mahale cultural team at the cultural program.

Dr. Shahidul Alam, a photographer of international repute, gives a close look on a sex worker, tortured in a safe home, after eviction from Tanbazar brothel in Narayanganj. The brothel, evicted in 1999, was the largest in Bangladesh and one of the biggest brothels in Asia. The exhibiton displayed many photos of systematic violence against women and marginal communities.

Dr. Shahidul Alam, a photographer of international repute, gives a close look on a sex worker, tortured in a safe home, after eviction from Tanbazar brothel in Narayanganj. The brothel, evicted in 1999, was the largest in Bangladesh and one of the biggest brothels in Asia. The exhibiton displayed many photos of systematic violence against women and marginal communities.