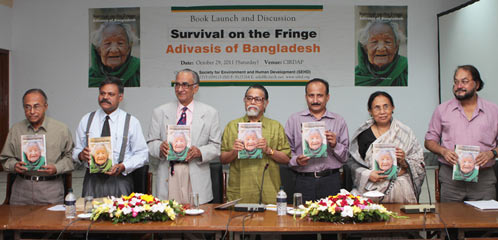

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) organized the photography exhibition “Ambushed by Greed: The Chak Story” which was shown from 23 to 29 June 2011. Held at Drik Gallery, the launching of the exhibition was piggybacked with a daylong seminar on the same theme.

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) organized the photography exhibition “Ambushed by Greed: The Chak Story” which was shown from 23 to 29 June 2011. Held at Drik Gallery, the launching of the exhibition was piggybacked with a daylong seminar on the same theme.

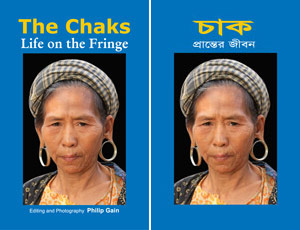

In his introductory remarks, Philip Gain, the photographer of the exhibition, explained how the images show an unprecedented ecological disaster that has come along with rubber monoculture, tobacco plantation, and the internal migration of Bangalis.

This has caused hardship and suffering to the Chaks of Bandarban. The Chaks, who number 3,000 in total, are concentrated in 21 villages in Naikhongchhari and Bandarban Sadar upazilas in the Bandarban Hill District. Distinctively different from other ethnic communities in Bangladesh, having a separate language and simple life, this tiny Chak community used to be real forest people, undisturbed and satisfied with their traditional jum agriculture for centuries. But Bangali settlements and the invasion of rubber and tobacco monoculture have opened up the area to the outsiders who have been plundering every natural resource from the Chak land. Consequently, the Chaks are being forced to abandon their homes, land, and traditional agriculture in remote areas.

Gain said that since 2008 he had been trekking through the remote Chak villages, particularly in Baishari Union, only to witness and record some of the devastating effects of rubber monoculture on the high land, and tobacco on the precious bits and pieces of flat land along the streams that the Chaks have used to grow vegetables and other crops.

The exhibition and the seminar were organized to share images and information and to appeal to the state to stop the destruction resulting from the invasion of modern agriculture, internal migration, and ill-conceived development strategies.

Mong Mong Chak, a former official of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Board (CHTB) and a well-known person in the Chak community observed that most of the profits from the rubber plantations go to the Bangalis. “The Chaks do not benefit from rubber plantation that has taken place on their traditional land; they are at the losing end. The rubber plantation also brings social ills—our women in particular feel disturbed due to movement of the employees who come to work at the rubber garden from outside,” said Mong Mong Chak.

Ching La Mong Chak, another leader of the Chak community referred to the government promises that rubber would generate new employment and road connections would improve. “But now we understand the promises were false. Moreover we have lost our land and the Chaks were compelled to desert a number of villages due to rubber cultivation. It brings outsiders to our localities who take away bamboo and trees from our village common forests,” complained Ching La Mong Chak.

Prof. Niaz Zaman, a writer on the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) women and backstrap weaving in particular, reflected that land grabbing has brought changes in every aspect of the Adivasi life in the CHT. The demography of the area has changed so that Bangalis are becoming almost equal in number to the Adivasis. This is dangerous as the Adivasis are gradually being branded as the outsiders and the Bangali settlements get legitimacy.

Prof. Niaz Zaman, a writer on the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) women and backstrap weaving in particular, reflected that land grabbing has brought changes in every aspect of the Adivasi life in the CHT. The demography of the area has changed so that Bangalis are becoming almost equal in number to the Adivasis. This is dangerous as the Adivasis are gradually being branded as the outsiders and the Bangali settlements get legitimacy.

“That the Adivasis are not constitutionally recognized is a political issue. They are not constitutionally recognized to avoid awarding them land rights. Both issues should be settled politically,” observed Prof. Mohsin. She urged for democratic practice among the political parties and institutions in the CHT.

Abir Abdullah, a professional photographer, reflected on the contents of the photos displayed. “The photos are telling that Philip Gain has taken the images not only as a photographer, but he has become one of the community who are at the centre of the exhibition,” observed Abdulah. “The mission of a photographer is to show what we do to nature and humans; the state is there to take necessary actions if things go wrong. In most instances, the photographers show the beauty of the CHT. This exhibition shows not only the beauty, but also the factors that cause human suffering. From this exhibition we understand how rubber and tobacco cultivation are severely affecting the Chak community.”

“We get little information about the small communities of CHT like Chak and Khyang. We are not well informed about the development projects in CHT. SEHD publications and events play a big role to fill up this gap,” said Goutam Dewan, chairperson of the Movement for the Protection of Forests and Land Rights. He pointed to the myth that huge cultivable land is still available in the CHT, which is used to settle Bangalis in the hills. He asked the CHT land commission to take steps for resolving the land disputes.

Khushi Kabir, the chair at the launching event, urged people to take advantage of the Right to Information Act in getting a fair picture of the land status in the Chak and other Adivasi-inhabited areas. He suggested that the photography exhibition is taken to a public place in order to draw greater attention to the Chak story.

In a plenary session, Philip Gain and Mong Mong Chak presented two keynote papers on the issues relating to the Chaks. In the first presentation, Philip Gain explained how rubber and tobacco cultivation in Bandarban Hill Tracts posed an outstanding threat to the Chaks and the ecology of the area. The second presentation on the Chak life by Mong Mong Chak reflected on the history, social system, economic activities, education, language and culture of the Chak community. “The Chaks are faced with financial hardship because much of their jum land and land for traditional horticulture have been lost to rubber cultivation. The forest resources are also declining. Moreover, they have difficulty selling their agricultural produces due to bad road network and transports”.

The plenary session was followed by two simultaneous workshops. Presided over by Mong Mong Chak and facilitated by Sudatta Bikash Tanchangya, the first workshop concentrated on struggle and future of the Chaks. Lucille Sircar and Partha Shankar Saha (senior researcher of SEHD) who have researched and written on the Chaks initiated the discussion. They talked on life and struggle of the Chaks and provided numerical account on them. The second workshop chaired by Dhung Cha Aung Chak from Baishari and facilitated by ZuamLian Amlai concentrated on rubber, tobacco and the Chak ecology. Journalist Buddyojyoti Chakma and training and program officer of SEHD Shekhar Kanti Ray initiated discussion on the socio-economic impact of tobacco and rubber cultivation.

Issues that emerged from the workshops were:

Rubber cultivation

- Rubber monoculture contributing to the destruction of natural forest and shrinking land available for jum and traditional horticulture.

- Rubber cultivation affecting the social security of the Chak community.

- Grazing land (chashila) and the land of vegetable cultivation at the foot of the hills are being destroyed

- Eviction of some villages due to expansion of rubber cultivation.

- Many Chaks becoming day-laborers at the rubber gardens established on their traditional land.

- Destruction of elephant habitat leading to wild animals attacking the Chak villages.

Tobacco cultivation

- Loss of fertility of the agricultural land.

- Use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers, residue of which seeps into the nearby streams resulting in the contamination of water and loss of aquatic resources.

- Negative impact of tobacco on human health.

Others

- Lack of resources, development and inefficiency of the local organizations.

- The Bengali and Rohingya settlements in the Chak area.

A statement of recommendations on the rights of the Chaks was adopted at the launch. See the Citizen Declaration and Recommendation Regarding the Rights of the Chaks for the full statement.

Press Reviews of Ambushed by Greed: The Chak Story

The Star – The Daily Star Weekend Magazine

New Age

Vorer Kagoj

Jai Jai Din

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) organized the photography exhibition “Ambushed by Greed: The Chak Story” which was shown from 23 to 29 June 2011. Held at Drik Gallery, the launching of the exhibition was piggybacked with a daylong seminar on the same theme.

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) organized the photography exhibition “Ambushed by Greed: The Chak Story” which was shown from 23 to 29 June 2011. Held at Drik Gallery, the launching of the exhibition was piggybacked with a daylong seminar on the same theme. Prof. Niaz Zaman, a writer on the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) women and backstrap weaving in particular, reflected that land grabbing has brought changes in every aspect of the Adivasi life in the CHT. The demography of the area has changed so that Bangalis are becoming almost equal in number to the Adivasis. This is dangerous as the Adivasis are gradually being branded as the outsiders and the Bangali settlements get legitimacy.

Prof. Niaz Zaman, a writer on the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) women and backstrap weaving in particular, reflected that land grabbing has brought changes in every aspect of the Adivasi life in the CHT. The demography of the area has changed so that Bangalis are becoming almost equal in number to the Adivasis. This is dangerous as the Adivasis are gradually being branded as the outsiders and the Bangali settlements get legitimacy.