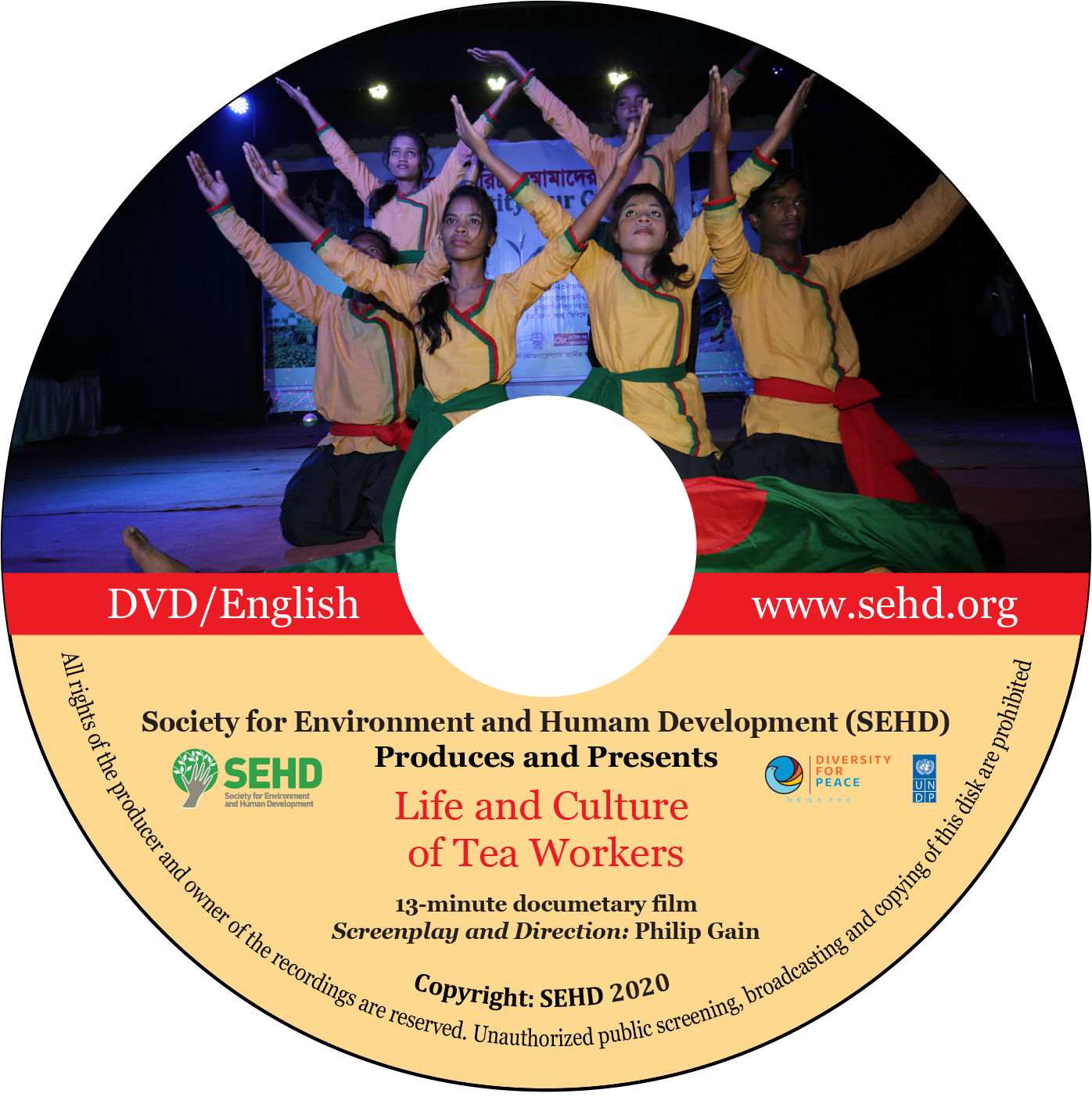

A section of those brought to the tea gardens of Assam by the British planters beginning more than 150 years ago are tea workers in today’s Bangladesh. Most of around 500,000 tea workers and their family members are Hindus and non-Bangalee. Labour lines in the tea gardens are their permanent residence. Most stunning of these tea workers are their diverse ethnic identity, language and culture. In its recent research Society for Environment and Human Development has identified around 80 smaller ethnic communities in the tea gardens. Of these communities, 23 are found in the official list of the ethnic communities.

A section of those brought to the tea gardens of Assam by the British planters beginning more than 150 years ago are tea workers in today’s Bangladesh. Most of around 500,000 tea workers and their family members are Hindus and non-Bangalee. Labour lines in the tea gardens are their permanent residence. Most stunning of these tea workers are their diverse ethnic identity, language and culture. In its recent research Society for Environment and Human Development has identified around 80 smaller ethnic communities in the tea gardens. Of these communities, 23 are found in the official list of the ethnic communities.

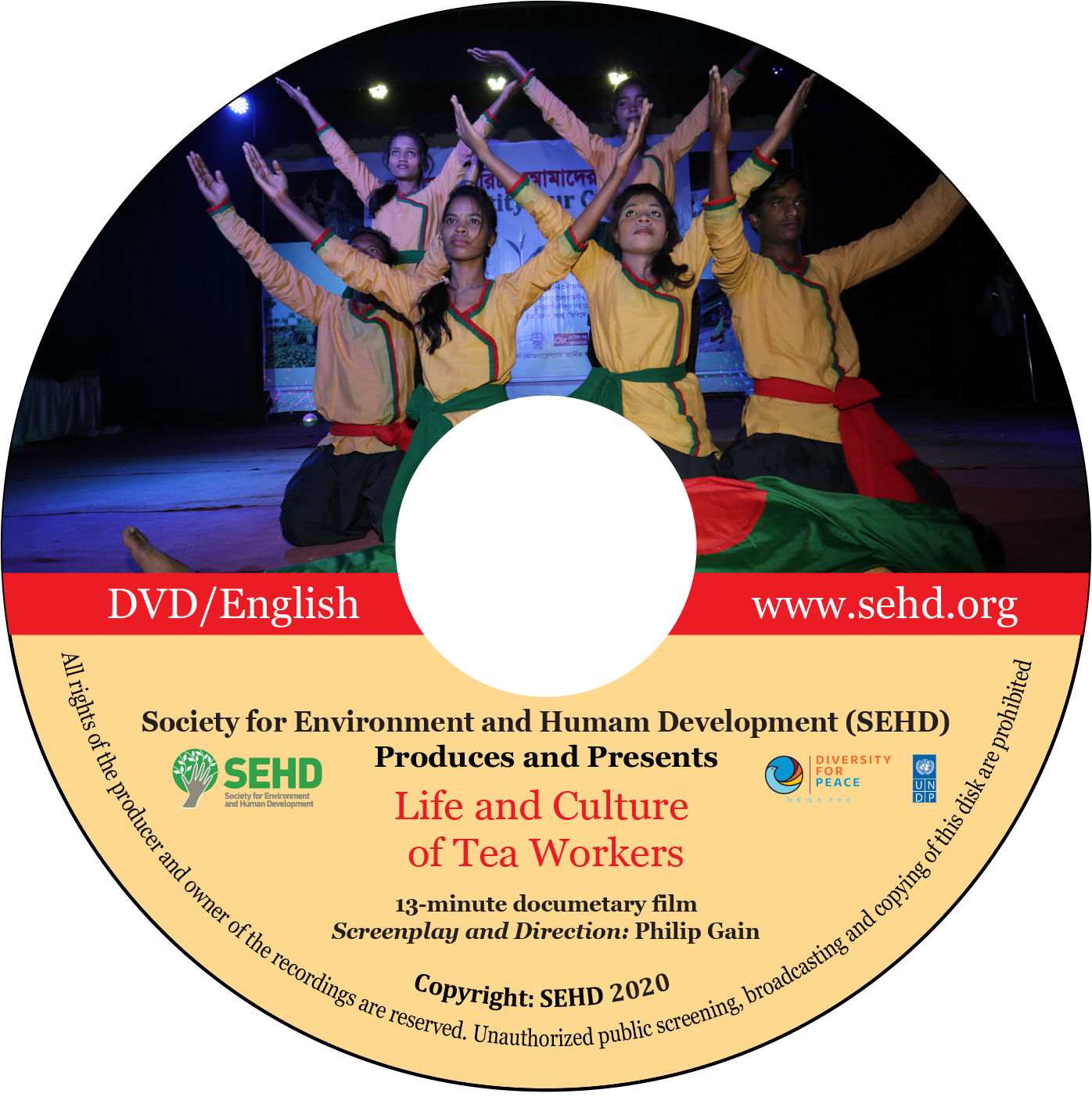

The documentary film shows us the life and diverse cultural heritage of the tea workers. The performances of different ethnic communities and language groups are very refreshing. For example, stick dance and branch dance are the key traditions among the Telegu-speaking Mandraji, Almik, Rajbhar, Tanti, Goala, Naidu, Kurmi, Teli and Reli communities. Stick dance is also popular among other communities. It is a common item in any cultural performance. Both boys and girls participate in stick dance. Branch dance is known as ‘Gentu Bajini’ among the Telegu. ‘Gentu’ means jumping and ‘Bajini’ means glorification. We see this in branch dance.

The attempts to keep these cultural traditions alive should be strengthened, trust the Telegu-speaking people.

The Shobdokor people show the colour of their culture with musical instruments. Their artists amuse people with their Dhamail and Shib-Gour dances in social and religious rituals, worships and festivals. Dhamail dance is indispensable in marriage ceremony in the Hindu community. Songs, dances and music we see among other communities in the tea gardens have no end.

Songs and dramas are not only entertaining, they also portray distress, pains and deprivation of the tea workers. Protik Theatre based in Deundi Tea Garden in Hobiganj district is a pioneer in this regard. More than sixty artists of Protik Theatre regularly practise culture and perform on stage. A glimpse of Nij Bhume Parabashi, a drama they perform, which portrays deprivation in the tea gardens is seen in this film. They excel also in patriotic songs and stage drama.

The Monipuri and Khasi are among their nearest neighbours. They are often-time seen together on the stage. The war dance of the Khasi and Mridanga and Rush dances of the Monipuri glisten the stage and fill the hearts of the viewers with joy.

The tea workers’ life is full of pain. Yet their songs, dances and dramas are so diverse and colourful. They share joy with cultural performances not only among themselves, but these are much appealing to their Bangalee neighbours as well. But sadly enough many of their languages and cultural heritages have lost due to neglect. Alongside Bangla language and Bangali culture, their diverse languages and culture need to be protected. The message of this documentary film is clear: cultural exchange can build bridge between the tea communities and the majority Bangalee and state sponsorship and attention of the majority community is crucial for protection of their culture.

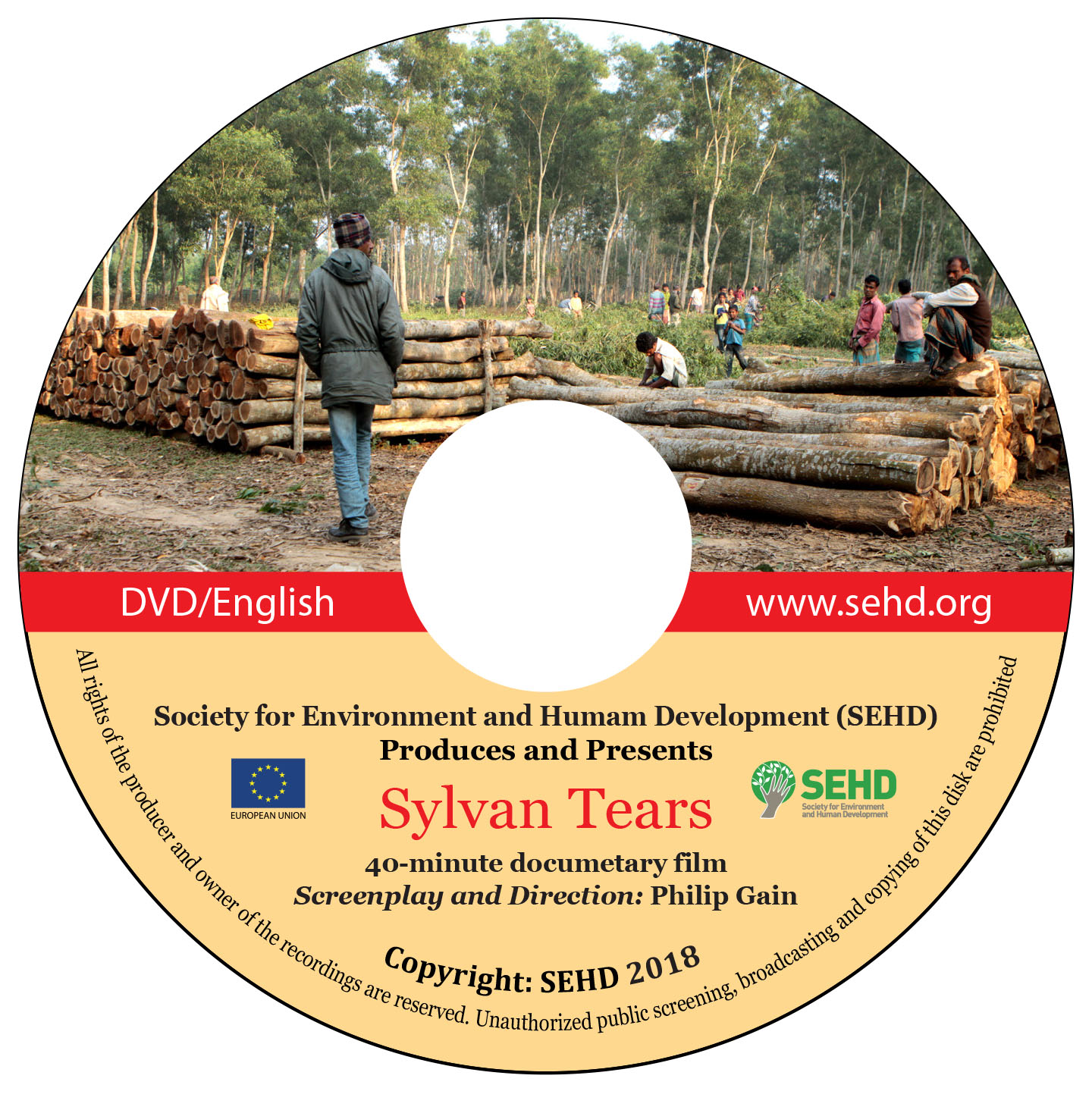

The documentary film, Aronner Artonad (Sylvan Tears), produced by Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) shows the current condition of the Modhupur sal forest, its demise and strained relationship between the forest villagers and the Forest Department. The stories of victims of physical violence including killings and forest cases and underlying factors for phenomenal destruction of Modhupur sal forest is at the centre of the documentary film. Of approximately 5,000 forest cases in entire Tangail district, 4,500 are in Modhupur sal forest area. The victims of forest cases narrate their insurmountable sufferings.

The documentary film, Aronner Artonad (Sylvan Tears), produced by Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) shows the current condition of the Modhupur sal forest, its demise and strained relationship between the forest villagers and the Forest Department. The stories of victims of physical violence including killings and forest cases and underlying factors for phenomenal destruction of Modhupur sal forest is at the centre of the documentary film. Of approximately 5,000 forest cases in entire Tangail district, 4,500 are in Modhupur sal forest area. The victims of forest cases narrate their insurmountable sufferings.

A section of those brought to the tea gardens of Assam by the British planters beginning more than 150 years ago are tea workers in today’s Bangladesh. Most of around 500,000 tea workers and their family members are Hindus and non-Bangalee. Labour lines in the tea gardens are their permanent residence. Most stunning of these tea workers are their diverse ethnic identity, language and culture. In its recent research Society for Environment and Human Development has identified around 80 smaller ethnic communities in the tea gardens. Of these communities, 23 are found in the official list of the ethnic communities.

A section of those brought to the tea gardens of Assam by the British planters beginning more than 150 years ago are tea workers in today’s Bangladesh. Most of around 500,000 tea workers and their family members are Hindus and non-Bangalee. Labour lines in the tea gardens are their permanent residence. Most stunning of these tea workers are their diverse ethnic identity, language and culture. In its recent research Society for Environment and Human Development has identified around 80 smaller ethnic communities in the tea gardens. Of these communities, 23 are found in the official list of the ethnic communities.

The Bede is a Muslim nomadic community that travels around the country to earn a living. Generally every year (during Eid-ul-Adha and/or elections), they gather in 75 locations of the country to meet their families and community members for one to two months. A floating people, the majority of the Bede is completely landless. Before modernisation, the Bede was highly regarded in Bangladesh society because of the service they provided to millions of people. As healthcare and medicines became more accessible and relatively cheaper, the traditional occupations of the Bede started to decline.

The Bede is a Muslim nomadic community that travels around the country to earn a living. Generally every year (during Eid-ul-Adha and/or elections), they gather in 75 locations of the country to meet their families and community members for one to two months. A floating people, the majority of the Bede is completely landless. Before modernisation, the Bede was highly regarded in Bangladesh society because of the service they provided to millions of people. As healthcare and medicines became more accessible and relatively cheaper, the traditional occupations of the Bede started to decline.

The Biharis are a Urdu-speaking Muslim minority community living in 70 camps in 13 districts of Bangladesh. They migrated from several states of India including Bihar at the time of partition of India. Still prejudiced by many and excluded by the larger society for their role in the independence war of Bangladesh, the majority of the Biharis live in congested and overpopulated camps where the rooms have expanded vertically for lack of space. Three or more generations of a Bihari family live in one tiny room where they sleep, cook and keep their belongings. Now officially recognized as citizens of Bangladesh, they are still deprived of many of their basic rights.

The Biharis are a Urdu-speaking Muslim minority community living in 70 camps in 13 districts of Bangladesh. They migrated from several states of India including Bihar at the time of partition of India. Still prejudiced by many and excluded by the larger society for their role in the independence war of Bangladesh, the majority of the Biharis live in congested and overpopulated camps where the rooms have expanded vertically for lack of space. Three or more generations of a Bihari family live in one tiny room where they sleep, cook and keep their belongings. Now officially recognized as citizens of Bangladesh, they are still deprived of many of their basic rights.

The Rishis are among the largest ‘untouchable’ or ‘Dalit’ communities in the Hindu world. They are lower caste Hindus who were traditionally skinners, leather workers and musicians. They are also known as Muchi, Chamar or Charmakar, which are considered derogatory terms for the community. Their traditional occupations of making and sewing shoes and skinning animals are considered impure and dirty. Even in this modern era, they are socially excluded because of their name and traditional way of living. In Bangladesh, the Rishis live in almost every district of Bangladesh with their highest concentration in Khulna division. The Rishis are still treated as ‘untouchables’ in some districts of the country.

The Rishis are among the largest ‘untouchable’ or ‘Dalit’ communities in the Hindu world. They are lower caste Hindus who were traditionally skinners, leather workers and musicians. They are also known as Muchi, Chamar or Charmakar, which are considered derogatory terms for the community. Their traditional occupations of making and sewing shoes and skinning animals are considered impure and dirty. Even in this modern era, they are socially excluded because of their name and traditional way of living. In Bangladesh, the Rishis live in almost every district of Bangladesh with their highest concentration in Khulna division. The Rishis are still treated as ‘untouchables’ in some districts of the country.